THREE

Frankenstein’s Youth

After the grueling homeschooling imposed on his children by Fabio Massimo, Dorina perceived that they needed a more official learning environment. She sent them off to boarding school in Rome, where the boys attended the famous Jesuit school at the Istituto Massimo alle Terme, housed in the beautiful palace that today belongs to the Roman National Museum.13 Much has been claimed about child abuse in such places, most of it unwarranted—at least in the sense of naked sexual abuse. In the sense of severity, I’m not so sure: The hardships imposed by the Fathers upon their pupils would certainly be considered child abuse nowadays.

To my speechless surprise, the Jesuit Web site fails to refer to Ettore but parades Luis Buñuel, the surrealist filmmaker, as a leading alumnus. (This, to me, is a bit like linking a pedophile site to the Vatican Web page.) Buñuel refers to his schooling with the Jesuits as “seven years of sickness, of complete lack of the most basic freedom, of evasion into erotic fantasy.” Such was the exalted milieu where Ettore spent his youth.

A talented boxer and one-time collaborator of Salvador Dali, Buñuel’s films include gems such as the details of the defecation method adopted by Simon of the Desert (a saint who spent forty years atop a twenty-meter-tall pillar preaching Christianity); a mock picture of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper enacted by tramps and taken with a unique camera (a woman’s vagina, it turns out); and a depiction of skeletons dressed in full Episcopal regalia being dragged across the ground by a pair of mules.

All of this the Jesuit fathers take in their stride with unflinching religious poise—which makes their silence regarding Ettore all the more poignant. Particularly since Ettore was indeed a believer—as attested by the 10 out of 10 mark for piety embellishing his school report card—and he remained so to the very end. In stark contrast to Buñuel, who titled the last chapter of his autobiography “Thank God I’m Still an Atheist.”

For his reverence, Ettore is now ignored by the Jesuit Web site. Ultimately, the Fathers know that he’s a greater threat than Buñuel to their view of the world. The dark matters Ettore stirred up when he disappeared in 1938 are so disturbing that the Fathers cannot take them in their stride. They inspire more fear than the jibes of an ostensible atheist.

Between the ages of eight and fifteen, Ettore was “internal” at the Istituto, boarding together with his brothers and cousins. At the age of twelve he skipped a year, spending the rest of his schooling in the same class as his brother Luciano (who was one year older). Then Dorina moved to Rome (leaving Fabio Massimo on his own in Catania for three years) to make sure her kids were being properly fed and looked after. By all accounts, Ettore didn’t make many friends during this period. He was often described as shy and introverted, although his mathematical stunts caused awe among the other students. At the age of eight, for example, Ettorino solved in his head a difficult exam problem that the final-year students had all failed to crack. But his reputation for genius was not fully reflected in his academic marks, which were good but not exceptional. And with awe came fear: Most of the other kids avoided him as if he were Frankenstein. He must have felt very lonely and isolated.

Like most people who have trouble relating to others, Ettore had a single friend to whom he was very close: Gastone Piqué. And it’s through Gastone’s accounts (given in TV interviews many years later) that we glimpse Ettore’s other side as a teenager: funny, even outgoing, when in the right company, and very affectionate to his few friends. He could imitate the Sicilian peasant accent to perfection, causing riotous laughter among his friends. He played football in the corridors of the family’s house with his brother. In what must have been a hell of a bash, they even trashed the family car. . . .

A family outing, August 1926. From left to right: Dorina, sisters Maria (on the ground) and Rosina, Ettore, Gastone Piqué, and Ettore’s maternal grandmother.

“The family always had lots of vacations. They were rituals,” Fabio tells me at Via Etnea. It wasn’t all hard work for the Majoranas, it appears. Work hard, play hard.

“Every year the family followed a well-defined pattern, led of course by Dorina. She’d say, “‘Next week we’re doing so-and-so,’” and next week she’d be marching her troops there.

“Typically, they’d spend the vendemmia—the annual picking of grapes and making of wine—at Passopisciaro, where the family vineyards were. The family owned a huge house there.”

I’ve visited the place, at the foot of Mount Etna. It’s stunning, and the wine—based on the Nerello Mascalese grape—is excellent. The modest main square is called Piazza Ettore Majorana, and it has a small statue of him in one corner. Some of the wine made there is renowned for coming from very old vines. I note that “old” means they were probably planted around the time Ettore was spending his days there.

“Then they’d spend a month each at two resorts: Abbazia (now in Croatia) and Montecatini, a nice little spa town in Tuscany. They traveled by car, driven by the family chauffeur, and stayed always at the same hotels, where the family was well known by the owners.

The vineyards of Passopisciaro, with Etna in the background. The wine is highly recommended.

“And finally for one month they’d travel in Europe, usually to Paris. Not always, but most of the time Paris. The family loved the French capital.”

“Not bad,” I thought.

“They all went?”

“Yes, as children and later as adults. She’d give the orders and they followed, even when they grew up. Except for my father, who was more independent as an adult. He had his own car, chased after girls, had his own life. . . .”

The signora chuckles.

I ask, “The family had cars?”

“Yes, the family loved cars. In fact, they had one of the first cars in Catania.”

In Italy they called them quadrocycles. This particular car was a Fiat 507, old style.

I continue in my mangled Italian:

“I hearded Ettore displayed a bad scar in his hand on his right-hand side . . .”

“ . . . because of a car crash! That’s true.”

I knew about this because it’s the departure point of a conspiracy theory. It appears that a certain vagrant, calling himself Tommaso Lípari, tramped along the Mazara del Vallo road, drank with immoderation, and . . . could do cubic roots in his head. Signore Lípari had a deep scar on his right hand and rumors spread that he wore a metal bracelet with 5/8/06 etched on it. It’s a contorted story, but Signore Lípari was not Ettore Majorana.

“Ettore had a big problem when he drove,” Fabio continues. “He couldn’t help steering toward wherever he was looking. If he chose to admire the landscape, everyone had to start shouting at him to look at the road instead.”

I smile: Horrible driving is a common feature of physicists. Erwin Schrödinger was effectively banned from driving (if his passengers stopped talking to him, he’d go off the road); Paul Dirac’s drives around Cambridge are still legendary; Leó Szilárd didn’t even have a license and had to be driven around while seeking Einstein’s endorsement of the atomic-bomb project.

“Ettore owned a license?”

“No, only my dad.”

“And how did they accidented the car?”

“A joke, a bunch of friends. . . . They all got into the car, not knowing about Ettore’s little handicap. Presumably he felt the need to admire a wall.”

We laugh heartily: No one was badly injured. But Ettore carried that distinctive scar on his right hand for the rest of his life.

“Grandma Dorina requested a full report and my dad said it had been himself driving. Of course, she knew what had happened and turned a blind eye.14 But to me this story shows that Ettore wasn’t just gloomy, as some picture him. He didn’t only have dark thoughts. He was also playful, at times. And a good friend to his friends. It’s been said that once, meeting with a friend worried to death about an exam, he made a bet that he could sit the exam in his friend’s place without anyone noticing. He won it.”

It’s obvious he had an irreverent side.

“Do you want me to show you something?”

Fabio picks up a book by a famous scholar—the leading proponent of the suicide theory explaining Ettore’s disappearance. The cover depicts a tortured-looking Ettore, with mournful eyes focused on the beyond.

“People love exaggerating Ettore’s dark side. Particularly these intellectuals. . . .” I get a whiff of scorn for nonscientific culture.

“Do you notice something funny?”

I scan the book but see nothing odd, except that Ettore looks very sad. From the family folders, Fabio produces the original photo. The photo employed on the book’s cover is a detail edited from a much larger print. Behind Ettore is Cousin Angelo. Lying on a bed in front of him is Fabio Massimo, Ettore’s father. Dead.

“Now, tell me who doesn’t look tortured and sad at his father’s wake?”

I tell him that this may have been done by the publisher without the author’s permission, but I make a mental note to chase down the author later.

Besides Luciano, Ettore had three other siblings: Rosina, Salvatore, and Maria. With such an overprotective mother, it’s hardly surprising that only two of the children ever married. The others lived with their mother until she died. Even Ettore lived with her until 1937, the year before he vanished.

The eldest, Rosina, married her German-language teacher in what I suspect must have been a bit of a scandal at the time. But today the family has the fondest memories of her “kidnapper,” a certain Werner Schultze, a German who came to live in Rome. He was never naturalized, but he refused to give himself up for conscription during World War II, even though he was still bound by German law. They had to hide him in the cellar throughout the war, his wife and the rest of the family knowing full well that he was risking death by firing squad if he was caught. When I asked Signora Nunni Cirino if he was against Hitler, her reply was simply that “he was against war.”

Salvatore Jr., the next in the brood, was primarily “a man of religion,” who left behind a huge pile of unpublished theological manuscripts detailing his interests in the logical foundations of religion. Some of the same issues appear in Ettore’s writings during his dark period between 1934 and 1937. It wasn’t just the random sightings that led his brothers, Luciano and Salvatore, to spend months looking for him in various monasteries in the vicinity of Naples after Ettore’s disappearance in March 1938.

Salvatore was also osservante, “practicing.” Every morning he went to mass at seven. He then returned home to study theology, reading and writing all day. Three days a week he went to the Regina Coeli prison to perform acts of charity for the inmates. He was a cross between a hermit and an intellectual. Signora Nunni Cirino sums it up this way: “He was a very odd person. With a golden heart . . . but different.” Her husband was less forgiving, calling him “poltrone”—“lazy bastard.”

Maria Majorana was the youngest sibling, and by all accounts she was a free soul in an environment not much given to great liberties. She was an outstanding pianist (Schumann and Debussy were her core repertoire), took part in amateur theater (Chekhov plays, mainly), and recited poetry (Verlaine and Mallarmé were her best loved). She’s been described as romantic and sensitive; deeply cultured. But she’s also been called a “head in the air.” Artistic talent in a house so full of science and politics was tolerated, but ultimately disapproved of.

As the youngest sister, she was always fussed over by Ettore, who did her mathematics homework (which she hated), gave her impromptu lessons in astronomy under the dark skies at Passopisciaro, and generally spoiled her. Being poetically inclined, she probably took the corresponding license, but here’s a beautiful memory she recorded (in the preface to Bruno Russo’s book on Ettore) from a summer holiday that she and Ettore spent together:

“It was a bright and beautiful day during our Summer vacation in Abbazia. We were bathing together and swam farther out than usual. Suddenly I saw Ettore pale, stiffen, as if he was about to faint. He looked totally vulnerable, defenseless and for a moment I panicked. Then I placed one hand under his chin to keep his head out of the water, and kept on swimming with the other, pulling him slowly towards the rocks. After a while he felt better and we returned together to the shore. But I’ll never forget that moment, the expression he had at that moment.”

One gets the impression that Ettore spent a lifetime on the verge of drowning.

When Ettore was sixteen, Dorina transferred him and Luciano to the Liceo Torquato Tasso, a school known for its academic achievement (today a major graffiti-art gallery). Ettore passed his final exams with flying colors and registered for an engineering degree at the age of seventeen. At the university he never went to lectures, simply “borrowing a book from a friend two days before each exam, skimming through it and getting top marks,” according to his friend Gastone, who was still a colleague. This nearly cost him a failing grade in drawing, where perhaps a bit more practice was required.

The Casina delle Rose, a charming place in Villa Borghesa (nowadays used as Rome’s cinematheque).

was here that Ettore’s gregarious side came out: funny and cultured, informal but sophisticated. His sense of humor was almost British—subtle but ultimately caustic and quietly antiestablishment.

The atmosphere during these gatherings was one of convivial chatting, but unavoidably Ettore’s deep sense of culture would surface during conversation. Ettore loved theater: Shakespeare and Pirandello were his favorites. Gastone comments, “He knew everything of Pirandello and when someone talked about him his eyes shone.” It’s not a coincidence that Ettore references Ibsen in his second letter to Professor Carrelli at the time of his disappearance, in which he compares himself to a heroine in an Ibsen play. We get more of this cultured humor in Ettore’s letters to Gastone. From Passopisciaro, he writes:Dear Gastone,

. . . I haven’t written before because I don’t like rushing, especially in certain things. You should be aware that I’ve given myself to the most scientific of the pastimes: I do exactly nothing and time goes by all the same. In truth I’m busy with an incredible number of things, but it being vile facts of the mind rather than facts of the world, better discount it.

If I don’t have an accident I’ll rejoin you in a few days. You shouldn’t believe it impossible that an accident may befall me in the flower of youth; on the contrary have it for very likely. From birth I’ve been an obstinately immature genius; time and experience have been useless and always will be, and nature won’t be as malign as to let me die prematurely of artherosclerosis.

But since vast and inscrutable is the sea of all my scorn for the sub-lunar world, it’s not without jubilation that I hurry to cross the threshold of your renowned living room in Via Montecatini, neither without trepidation will I drink the bitter chalice to the last drop.

A hug,

Ettore.

From the Tuscan spa town of Montecatini, lodging at Hotel Tamerici—a masterpiece of bad taste—Ettore further informs his friend of the following:Dear Gastone,

I stoically drank three drops of bitter water, then another ten, then six glasses.

I am in waiting; may God take care of me.

The languor that pervades me lends to my soul the tenderest feelings. How much gentleness in the respite of a man who has sipped a liter and a quarter of purgative water! . . . The delicate fascination of your pretty region and of those who people it and a subtle sense of nostalgia complete the spell.

I will see you in three days (perhaps tomorrow I’ll book a room) and my mind rekindles with that thought; because there is no brighter joy for me than to see you.

Ettore

PS: The duty calls me. Goodbye.

Later he goes to see his friend at the nearby beach resort of Viareggio. He writes in a postcard:

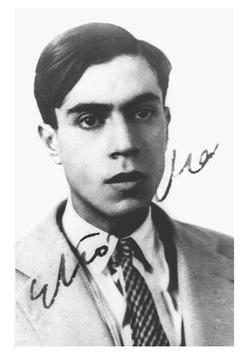

An autographed photo of the young Ettore Majorana.

Dear Gastone,

I’ll come probably tomorrow, in the afternoon. I’ll actively and orderly look for you: 1stat number 42, 2ndat the Gatto Nero, 3rdat the Lido Felice, 4thunder those windows.

With affectionate salutations,

Ettore.

The last reference is to a lady Gastone was courting (removing suspicions of homosexuality between the two). And it’s Gastone himself that gives us an insight into Ettore’s feelings in that quarter. In an interview he said, “Since he was not physically beautiful, he had a complex toward women. Because beautiful, properly, he wasn’t; indeed, he was rather ugly. And I can tell you that at the Liceo there was a girl, the daughter of a prefect, a very intelligent girl, and this young man, so prodigious, such a genius, truly attracted her. But he did nothing, even avoided her, because he was a victim of his inferiority complex, due to his ugliness.”

I have no idea what the taste in men was at the time, or why Ettore thought he didn’t fit it. But that his best friend agrees he was ugly is quite damning. It’s significant that Ettore failed his compulsory military medical for being too slim, having a “chest too small.”

Ettore smoked a lot, but he wasn’t a great drinker. Too bad—it might have helped him loosen up with women. Maybe his tragedy would not have happened if he’d enjoyed a more substantial drop than the civilized glasses of wine he sipped at the Casina delle Rose.

How, then, to conciliate Ettore’s two sides: the timid and the gregarious?

Jokes and pranks aside, one should not get the impression that Ettore’s youth was a happy one. It was dire. Between the priests and his parents, his basic humanity was destroyed. He was brought up by social outcasts and grew monstrously distorted, lacking social skills and independence, full of ineptitude. People like him—when they don’t become criminals, drug addicts, or psychopaths—can’t help being intellectually superior. But they’re “Frankensteins,” artificially gifted, clever “against nature.” And like the literary monster, behind the bestial genius lies a very different nature: tender in a way that can never be fully realized; longing for love, knowing full well that it will always be denied; a furnace of kind emotions that the ogre exterior will always screen. Occasionally, as in the gothic tale, a blind man who can’t see their ugliness will hear out their plight and show sympathy; only for others to step in and inflict further humiliation.

This may explain Ettore’s later demise. Alloyed with such a “monstrous” existence, it is not surprising to find aggressive emotions geared toward destruction or, worse, self-destruction. Behind a facade of sadness and depression there’s a drive to run away, to escape: whether by suicide, disappearance, or just a clean break with the family. It’s a drastic and never guilt-free decision: to sever all ties with those to whom we owe our existence. But perhaps it would have been worth the price for Ettore, if it achieved the one thing he most wanted: to annul that grim existence, trading it in for a new one.

One can hear in the runaway Ettore of several years later that voice of longing and frustrated love. At nineteen he thought he was ugly, but perhaps he’d been made ugly by his environment. Perhaps he was just an ugly duckling, a swan accidentally left in the wrong nest, who’d one day reveal his true nature. By evading his family, he was also burning a baby—himself, in that cradle he may have grown to despise. His urge to escape is brutally patent in Fabio’s words at Via Etnea when I question him about his father’s efforts in 1938. He says: “Do you know the crux of the problem? No one searched for Ettore more than my father. He did everything, everything he could to locate him and help him back. But after one year, he didn’t search anymore. He understood that if Ettore hadn’t returned, it was because he wanted to be far away from the family, on his own. It was his choice. And they should all respect it.”

Comically, it was only after Ettore disappeared and acquired the notoriety of a ghost that numerous women emerged, claiming to have dated him. At least two Theories of What Happened to Ettore employ a hidden lady,15 but both clash tremendously with everything we know about Ettore’s personality and hang-ups. This is not to say that there were no women in his life—real, well-documented human beings.

On the contrary, there were. And one of them was present, filling his mind, on the day he vanished from Naples in 1938. We will have a unique chance to meet her, in due course. She makes Ettore fit the Frankenstein bill like a glove: the monster full of kind emotions who is condemned to hide and observe the happiness of others through a window, longing for a love that could never be his.